What

is immediately apparent on entering Bhutan is the clarity of

difference. The country was almost entirely isolated from the

more modern outside world until the early 1960s and has subsequently

undergone only very partial integration in line with the measured

and balanced development policy pursued. It is only one generation

removed from what might be termed a pre-modern condition, and

for many their overall situation - although considerably improved

in certain important respects - has not changed that dramatically.

The prevailing culture, therefore, not only draws on certain

aspects of the past for inspiration, but also bears an unusually

close resemblance to a long-established undiluted tradition.

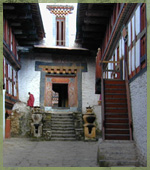

Within this context neither the positions occupied by religion

and the monarchy, or the perpetuation of dress, architecture,

handicraft and overall social organization appear as particularly

outdated throwbacks. What

is immediately apparent on entering Bhutan is the clarity of

difference. The country was almost entirely isolated from the

more modern outside world until the early 1960s and has subsequently

undergone only very partial integration in line with the measured

and balanced development policy pursued. It is only one generation

removed from what might be termed a pre-modern condition, and

for many their overall situation - although considerably improved

in certain important respects - has not changed that dramatically.

The prevailing culture, therefore, not only draws on certain

aspects of the past for inspiration, but also bears an unusually

close resemblance to a long-established undiluted tradition.

Within this context neither the positions occupied by religion

and the monarchy, or the perpetuation of dress, architecture,

handicraft and overall social organization appear as particularly

outdated throwbacks.

There is a rare coherence and sense of balance in current

cultural conditions. Throughout the world pockets of indigenous

culture perpetuate. However, it is unusual that an entire

nation remains collectively so connected to its traditions,

and significant dislocations have not yet occurred across

time and space. Much of Bhutanese history retains direct contemporary

relevance, rather than being a record of a remote and incongruent

past. Furthermore, a complete division has not yet occurred

between modern urban and traditional rural cultural systems.

Individual identities remain firmly rooted within established

structures and belief systems, reflected in a lack of self-consciousness,

an underlying self-confidence and the high return rate of

students studying overseas.

The foundations of contemporary Bhutanese culture lie with

several closely interrelated traditional legacies: ethnicity,

Buddhism, hierarchy, community and self-sufficiency. There

are three main ethnic groups - the Sharchops of Indo-Mongoloid

origin, the Ngalops of Tibetan origin and the Lhotsams of

Nepali origin - and there remain a few distanced tribal communities.

The most profound cultural influences arrived with the Tibetan

migration. The Ngalops are the dominant group within the country,

over the centuries bringing with them Tibetan Buddhism, artistic

and more functional practices. The earlier settled Sharchops

were converted to Buddhism and subsequently integrated within

a centralized Ngalop dominated nation. The Lhotsams' arrival

is much more recent - over the course of the Twentieth Century

- and, due to Hindu religious belief, the relative strength

of an existing culture and their concentration in the south

of the country, many have not become wholly assimilated within

the prevailing Ngalop dominated national culture. Although

the national language is Dzongkha - belonging to the Tibetan

language family and historically spoken only in the west of

the country - Nepali (and to a lesser extent Sharchop) remain

widely spoken. The national newspaper, the Kuensel, represents

the major language sets, being published in Dzongkha, Nepali

and English, which has become a principal language of instruction.

Since its arrival in the Seventh Century and gradual diffusion,

Tantric Buddhism has underpinned individual and collective

outlooks. The relationship between religion and culture was

and remains particularly intimate due to the both the holistic

approach to life that Buddhism implies, and the enhanced significance

attributed to religion within traditional societies. In the

sense that Buddhism, especially in its tantric form, lays

out a blueprint for correct thoughts and actions (and therefore

correct values), it has strongly informed the development

of political and social institutions. There remains an unusual

consistency between respective elements of a supporting cultural

system. Furthermore, since the natural environment, art forms,

rituals and ceremonies are all connected to religion, Buddhism

has been the fundamental influence on material as well and

psychological aspects of culture.

Politics and religion remain deeply interrelated. Whereas

Bhutanese society is predominantly egalitarian, the legitimacy

to rule is divinely determined. This implies a very steep

natural hierarchy, with a significant division between those

to whom divine legitimacy has been attributed - high rinpoches,

the King and blood relations - and everyone else. Those in

authority possess an awareness of their responsibility and

the reciprocal nature of implied relationships. Around these

centers a system of court politics has developed, where power

is given through the nature of the relationship with the source.

This implies a very vertical and narrow central political

hierarchy. Although the political system is being reformed

- and new hierarchies are developing related to wealth and

more broad-based notions of status - power remains concentrated.

Other more aesthetic cultural forms are essentially passed

from the top-down, for example fashion and architectural style.

The basic social structure remains highly devolved. Scattered

self-reliant village communities were traditionally relatively

distanced from each other and monastic-fortress power bases.

This has led to highly localized and self-contained worldviews

and life-worlds. A restricted perspective on the material

world has served to accentuate a village's relationship with

itself and the spiritual domain. Local stories and superstitions

- many with fantastic themes and twists - thrive within a

rich storytelling tradition. Religious aspects are deeply

embodied within village systems, varying from a temple or

priest to an auspicious location and interesting explanation.

There remains an immense multiplicity and diversity of cultural

practice, concentrated around respective communities. A number

of local dialects are spoken and an integrated extended family

system remains firmly in place.

The idea of community remains extremely strong, being a robust

source of identity. Where everyone knows everyone else and

their personal histories, one is more likely to suffer from

claustrophobia than alienation. Even when transferred to an

urban environment - particularly among the majority first

and second-generation migrant - most people still associate

with a particular region and village, and a similar sense

of community has evolved within these new settlements. Traditional

values possess a high respect for age, history, local deity,

learning, face and family. The essential self-reliance of

individual villages underlies traditional economic systems

that were non-monetized, subsistence-based and internally

self-sufficient. It is no coincidence that communities with

a trading culture - for example the people of Laya and Chapcha

- have proved more successful at taking advantage of emerging

business opportunities.

|